Table of Contents

Rail travel in Japan from a passenger’s point of view

It is undisputed that, in view of the ecological crisis, we must make our mobility more sustainable and environmentally friendly. Railways in local and long-distance transport play an important, if not the most important, role in this. There is hardly a more efficient way to transport large groups of people. And yet it is almost a national sport in Germany to get worked up about local public transport and the Deutsche Bahn, Germany’s state-owned railway operator. Delayed trains, unfriendly staff, dirty trains and stations - there are many reasons to complain. In this text, I would like to report from the promised land of rail transport, where I have been living for almost five years now - from Japan.

What makes rail travel in Japan so special and so pleasant? How does the experience as a passenger in Japan differ from the German experience? I will describe many individual points that constitute an overall picture quite different from the experience of German rail travel. Some of these points could only be implemented with a great deal of effort, especially in terms of personnel or train equipment. Others, in my view, could be implemented with relatively little effort. The point of this text is thus not to make people in other countries jealous, but rather to show that many annoyances we take for granted in rail travel, are actually not inevitable.

My experiences primarily refer to the Greater Tokyo area, which certainly enjoys a certain special status in Japan. Nevertheless, I can confirm from many trips in Japan, also in rural areas, that many of the experiences described here can be transferred to the whole of Japan.

Service culture

In general, the level of service in Japan is extremely high, be it in public services, in restaurants or on trains. Politeness and helpfulness are the rule, and the customer is always king. Even if you have little or no knowledge of Japanese, the staff will always be polite and try to be helpful.

The first thing you notice in Japan as a whole, but especially on the train, is that service staff is everywhere. On the platforms, you often find service staff, in most stations there are information points at all exits and almost every ticket gate features a booth with staff. By comparison, in Cologne-Ehrenfeld, after all one of the most important S-Bahn stations in Cologne, I did not encounter a single employee in five years of daily commuting. The job description of stationmaster was abolished in Germany a long time ago anyway.

This difference certainly has to do with another observation: compared to German stations, Japanese train stations are very clean. There are hardly ever litter garbage cans, partly for fear of bomb attacks1. Yet you will have a hard time finding any trash lying around, thanks to the discipline of the Japanese and regular cleaning of the stations. These also include the free (!) toilets, which are always available and usually even have changing tables for babies.

Another important point is the information culture: in Tokyo, most signs in train stations are available in four languages: Japanese, Chinese, Korean and English. In rural areas, this is not always the case, but important information is almost always translated into English as well. Announcements are also available in English at larger stations and in Tokyo. And if you do have problems remembering the name of a station: the stations of a line are numbered consecutively and bear the abbreviation of the line; so in case of doubt, just remember the abbreviation.

Orientation in the stations is facilitated, for example, by the fact that everything of importance (railroad lines, interchanges, exits, etc.) is signposted, and on these signs, in addition, the distances are usually indicated. This is important information in Tokyo’s huge, interlocking train stations, which often bundle the stations of several train companies.

Another example of the well thought-out information culture: on the platforms of the Tokyo subway, signs for all stations on the respective line provide information on which car is best to board in order to change trains as quickly as possible at the destination station, to get to the toilets or to reach the elevators. All of this serves one purpose: to make it as easy as possible for passengers to move swiftly through the rail system, thereby making it possible to handle the massive passenger loads in Tokyo and elsewhere in Japan.

Organisation

Japanese trains are optimized for functionality in both local and long-distance service. In most commuter trains, suburban trains and subways, this means that there is a lot of standing room and relatively few seats (mostly on opposite benches facing away from the windows), with few exceptions there are no stairs to climb on trains and the interior is unadorned and uniform. The torture of lugging suitcases and baby carriages up and down stairs in Germany’s double-decker cars is simply eliminated.

In the Shinkansen, too, functionality and maximum capacity have priority. The famous high-speed trains offer five seats in a row while still providing a wider aisle and even more legroom than the German ICE. In addition, the Shinkansen has toilets, baby-changing facilities and washbasins in every carriage. Parents who have experienced walking through half an ICE train in search of one of the planks that the Deutsche Bahn offers as changing tables will appreciate this.

In Japan, standardization and reliability are trumps. Trains in the big urban areas are always built the same way: Subways and commuter trains always have 8 or 10 cars; Shinkansen always have 8 or 16 cars. The unreserved seats in the Shinkansen are always in carriages 1 to 3 (and there are no reserved seats there either); conversely, all other carriages can only be used with seat reservations (available for a relatively small surcharge). Row 1 in the Shinkansen is always at the beginning or end (the seats are simply turned around in the Shinkansen at the terminus, so that the train can depart again directly) and the rows are systematically numbered, similar to airplanes. No comparison with German long-distance traffic, where car and seat numbers are selected and randomly distributed without any discernible system 3, regularly causing great confusion, conflicts and congestion when boarding.

Another important point is the organization of the platforms. Anyone who has ever ridden a train in Germany knows the game when the train arrives: the passengers are more or less equally distributed on the platform, roughly where they expect their car to be. When the train arrives, a wild scramble begins, since one never knows exactly where the cars will stop, followed by large crowds at each door and fights over who gets to enter the car first. Not to mention the regularly occurring classic “the train is operating in reverse car order today”.

How pleasantly different the procedure is in Japan: On the platform, it is clearly marked where which car stops (both on the Shinkansen and on every commuter train and subway). So you can stand in exactly the right place, which is always in an orderly queue. No rushing across the platform because of “reversed car order” or, heaven forbid, because a car is missing. Thus, even the Shinkansen can limit its standing times at stations to between 90 seconds and 2 minutes.

This reliability also applies to platforms in general: Local and long-distance lines have permanently assigned platforms and operate on separate tracks, strictly speaking even in separate, but connected, stations. A situation like in Germany, where local, long-distance and sometimes even freight trains share platforms, is unthinkable in Japan.

Punctuality

Japanese trains are very punctual. In the Greater Tokyo area, you may not always notice it because of the tight schedule (some trains run every 2 minutes), but you can absolutely rely on departure times. The punctuality of the Shinkansen is already world-famous. For example, in 2018, the average delay of the Tokaido Shinkansen (which runs between Tokyo and Osaka) was about 0.7 minutes 4. On this route, by the way, the Shinkansen runs every 10 minutes during the day. Obviously, this changes the entire travel planning as a passenger. Whereas in Germany you should allow at least 10 to 15 minutes for transfers and, if in doubt, better pick one or two alternative connections, in Japan you can be absolutely sure that connections and transfers will work out.

The stress that accompanies every train journey in Germany - constantly checking whether you are currently late, whether you can make your connections, what alternatives you still have - is simply unknown. The most important factor when changing trains in Japan is not possible delays, but at most the sometimes large stations in the urban centers, and the high passenger numbers, which can make changing trains difficult.

Tickets

Long-distance transport in Japan (i.e., the Shinkansen) is more expensive than in Germany, while local transport is significantly cheaper. With the Shinkansen, there are no discount systems and savings prices as in Germany, and there is also no equivalent to the Bahncard, so you basically pay a fixed price 5. This applies regardless of the time of booking, the route Tokyo-Osaka (travel time 2h 27 min with the fastest variant, approx. 515 km), for example, costs approx. 14,000 yen, the equivalent of 107 euros.

For this you travel on a very fast train that leaves every 10 minutes during the day 6. So, if you don’t have a seat reservation, you can treat the Shinkansen almost like a commuter train: you just take the next train that comes along.

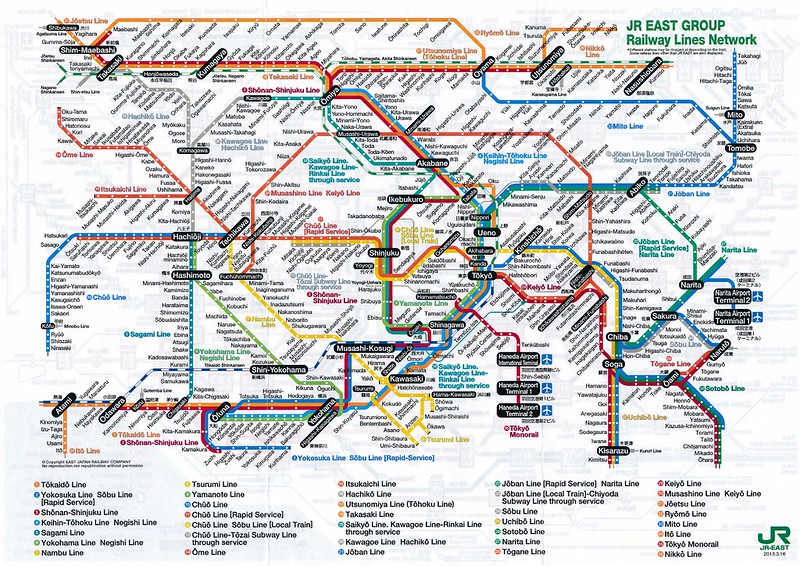

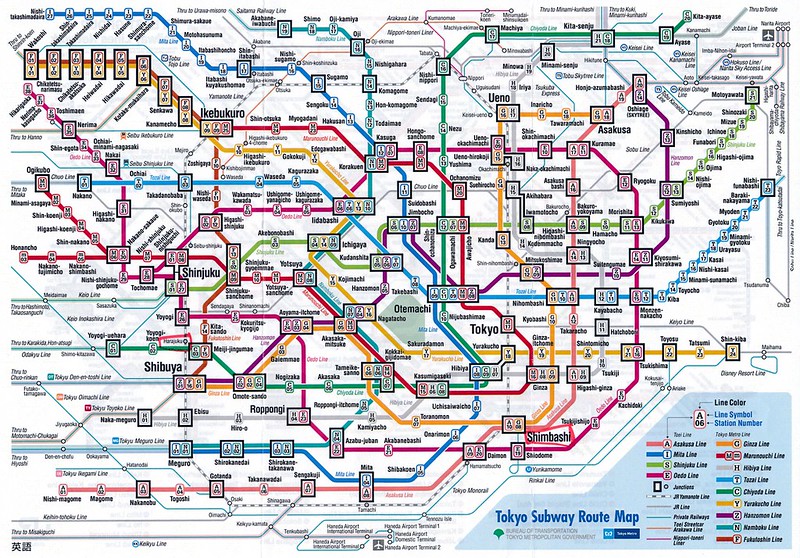

Tokyo’s mass transit system can boggle the mind at first glance. There is a subway system with 13 lines operated by two companies. In addition, there is the commuter train system of the semi-public Japan Railways with a total of 23 lines in the Tokyo metropolitan area. And on top of that, there are the lines of the private railroad companies, which operate a total of 55 lines. In addition, depending on the line, up to 5-stage systems with express trains. The good news is: these many lines are interconnected and often you just stay on the train while the line designation changes, because the railroad companies cooperate with each other and exchange the trains quasi during operation.

In addition, it is incredibly cheap to use this huge, complex system. Ticket prices on the trains are staggered according to distance. Tickets on the subway cost between 170 (up to 6km, 1.30 euros) and 320 yen (from 32km, 2.46 euros). For example, from Tokyo station to Shinjuku (the busiest station in the world), you pay 276 yen (2.12 euros) for about 25 minutes on the subway 7. By comparison, a single ride in Cologne costs 3 euros, and 3.40 euros in Munich. Both cities would be about the size of two (of the 23) districts in Tokyo.

Variable pricing on mass transit may seem complicated at first, but the good news is that all these tickets require is a chip card that you charge with money (or link directly to your credit card) and can then use on virtually all trains throughout Japan. Except for special trains (including the Shinkansen), all you have to do is check in and out at the ticket gate (all platforms are screened by gates), and the money is automatically debited. No long search for the right fare, no research regarding interconnection limits, transition tickets, etc., all these stress factors do not exist. There are ticket machines, but you really only need them to charge your chip card or to purchase a special time card (day or special tourist cards). The ticket gates also mean that ticket checks are not necessary and fare evasion is virtually eliminated.

Conclusion

This text describes my experiences as a passenger on rail transport in Japan. Rail travel in Japan is a real delight, from the service culture, the organization and punctuality of the traffic to the ticket prices: you can get around extremely well by train in Japan, because most of the stress factors that you know from Germany are simply unknown. On the one hand, this is thanks to the objectively higher quality of the train service, and on the other hand to the many small details that make train travel easier.

This does not necessarily mean that you do not need a car in Japan. In Tokyo and other metropolitan areas, a car is definitely not necessary, but in the countryside the situation can be quite different. Nevertheless, I would argue that even in rural areas, public transportation, if you add buses, has significantly higher quality than in Germany.

So can Japan be taken as an unqualified model for Germany (or other countries)? I think there are many things that could only be improved through massive investment in infrastructure, such as punctuality and high frequency. The reintroduction of stationmasters or more staff at stations in general is of course a question of cost, but it’s also a question of attitude toward the customer: Do I want to fob off passengers with monotonous, automated announcements? Is it acceptable that freight trains rush through on platforms without warning and thus endanger passengers? Do I leave my customers alone with their questions and needs?

Other points seem to be primarily a question of attitude, especially with regard to the service culture. And still other points could certainly be changed by organizing transport differently, for example fixed and reliable train lengths, seat and carriage numbers, fixed tracks for rail lines, better signage at stations.

In summary, I would say that countries such as Germany should definitely take Japan as an example. Taking Germany as an example, there are certainly many differences between the two countries, especially in geography and the resulting topology of the rail network. But there are also similarities, for example both countries have powerful car industries and yet in Japan, unlike in Germany (or the US), they have decided against basing transport planning primarily on the car. In a follow-up article, I will look at how and why the railroad system works in Japan and what Germany could learn from Japan.

References

1 After the poison gas attack in the Tokyo subway in 1995, trash cans in train stations were abolished. See for example https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-05-23/where-are-all-the-trash-cans-in-japanese-cities.

2 See for example https://expatsguide.jp/articles/features/tokyorailhacks/.

3 The infamous car numbers 22-27,35-39 on the ICE and the seat numbers on long distance German trains that seem to be randomly thrown on the seats.

4 https://global.jr-central.co.jp/en/company/ir/annualreport/_pdf/annualreport2018.pdf

5 There are various ways to save a bit of money, but that is limited to discounts of maybe 10 percent at most, so no comparison to the German system.

6 Unlike the ICE, which reaches really high speeds only on a few routes, the Shinkansen reaches top speeds of 285 km/h on said Tokyo-Osaka route.