Table of Contents

- Which paradigm do we need to save the world?

- How did we get here?

- What to do? The conservative approach

- What to do? The revolutionary approach

- Conclusion

- References

Which paradigm will save the world?

We can’t look past the evidence anymore - we are in the middle of a climate crisis, not in a near or distant future, the crisis is here and manifests itself in many aspects. But this is not only a climate crisis, this is an ecological crisis.

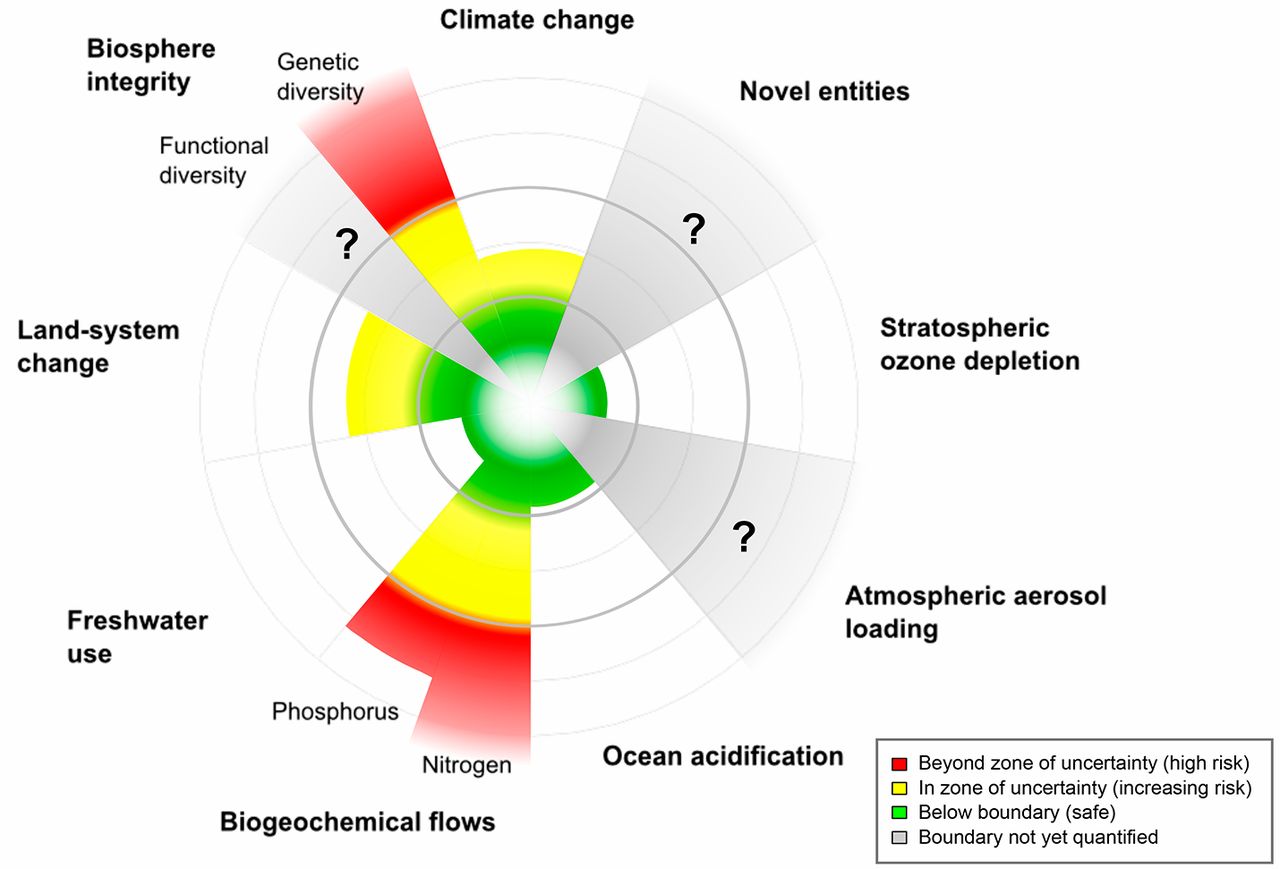

In 2009, scientists defined nine planetary boundaries 1 which were revised in 2015 2. These boundaries are related to different aspects of the earth’s ecosystem and define, with uncertainty, thresholds that should not be crossed by humanity. If crossed, we are likely to enter an unstable state of nature on earth, risking the future of human life on earth.

The climate crisis is just one of three planetary boundaries 2 that humanity has already crossed. The other two are Biosphere integrity (particularly genetic diversity of species) and Biogeochemical flows (the Nitrogen and Phosphorus cycles) (see Figure 1). There is no other way to say this: we are systematically destroying nature and the earth’s ecosystem.

How did we get here? And what do we need to do? In this text, I’d like to sketch which worldview has led us to the current situation and what different approaches to a solution are being discussed.

This text is not about discussing detailed aspects of a solution or evaluate technical innovations. Rather than discussing those details, I am here concerned with the question: which way of thinking fuels the ecological devastation? How can we change our mindset to improve our actions and avoid the collaps of ecosystems on earth? There is the technocratic idea that we just need to “follow the science” and put scientific insights into action. However, to act politically, and only this can prevent a further escalation of the ecocrisis, we need a normative idea where we want to go and an ideological basis. We need a narrative that guides us in the right direction.

How did we get here?

The ideology of the West, formed by Judaism and Christianity, takes a dominant stance with respect to nature. The bible says: God blessed them and said to them, ‘Be fruitful and increase in number; fill the earth and subdue it. Rule over the fish in the sea and the birds in the sky and over every living creature that moves on the ground.” (Genesis 1, 28, NIV). In this view, human beings are not actually part of nature, rather they are apart or even above it. Nature is defined as an antagonism to human civilization and human culture. It is a passive stage for human actions and an (inifite) reservoir of resources that humanity is supposed to exploit.

The phiolosphers in the Age of Enlightenment did not drop this idea. Despite the triumph of the heliocentric system and the Theory of Evolution (in the 19th century), we did not reject the idea of the singularity of humanity. Rather, the humanistic movement elevated the human beings themselves to gods, if you follow Yuval Noah Harari 3, 4. This idea continues to be alive in our contemporary society, which is obviously heavily influenced by the Age of Enlightenment.

Our economy relies to a large degree on the use of natural resources, for instance as a provider of nutrients or as a source of fossil fuels such as coal and oil. Ecological destruction is seen as externalities, i.e., factors that have not been integrated into the market (yet). Even on a small scale, social and economic interests on the one hand and protection of nature are essentially seen as opposing interests that need to be balanced (at least). For example, it is legally required in Germany to compensate areas designated for buildings with areas left to nature, as if ecosystems could be ripped apart and put together at will.

This narrative has led us to the situation of today: humanity has subdued all of earth and, thanks to technological progress and unleashing immense energies, became the dominating force in the world. To a degree that there is a proposal to name the current geological epoch of the earth the “Anthropocene”.

What to do? The conservative approach

The conservative approach frames the distastrous destruction of earth as a technological challenge rather than a social and ideological crisis. The ecocrisis is not a sign of failure of our capitalistic economic system, it is a logical stage of development. According to this view, economies develop from an agrarian economy to a polluting industrial society and finally to service economy. In this service economy, polluting ways of production play a minor role and industries, fueled by technological progress which are enabled by generated wealth, achieve production in a sustainable way. This requires a “green growth”, with decoupling of emissions of greenhouse gases and economic growth, strongly correlated in the past.

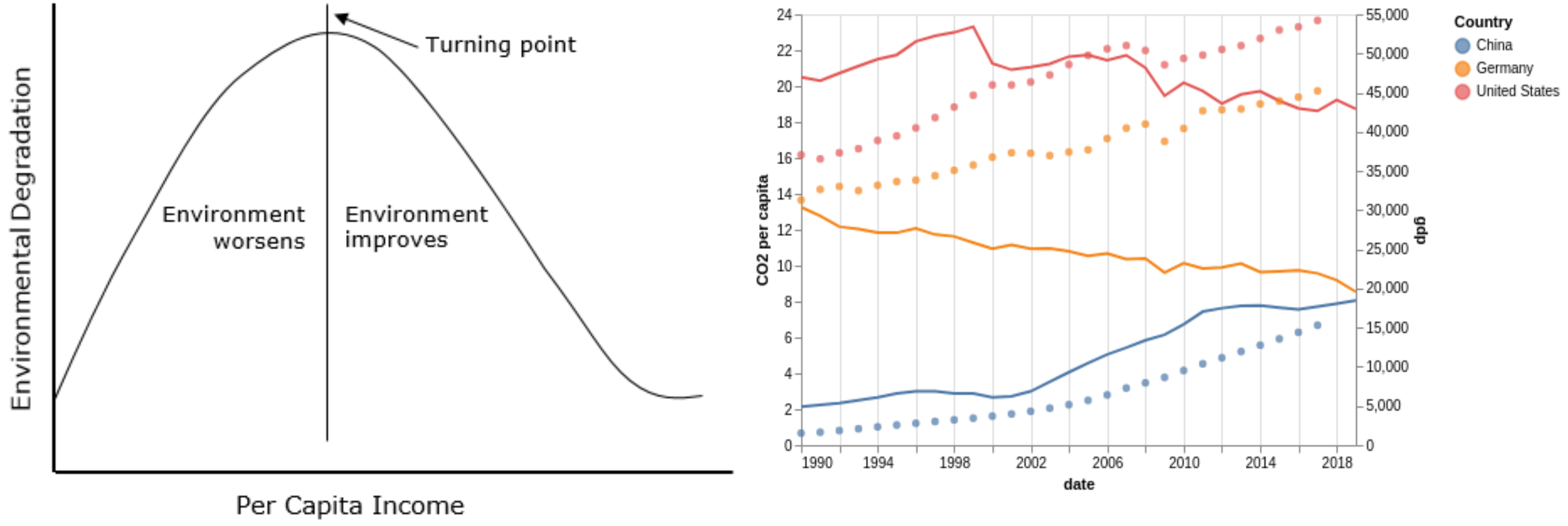

The environmental Kuznets curve (see Figure 2) provides the theoretical basis for this ideology. It hypothesizes that the environmental stress of an economy first increases in with growing gross domestic product (GDP), then reaches a peak and decreases afterwards. Multiple possible reasons for such an effect come to mind. For instance, there could be a growing desire for environmental protection of people with increasing wealth. Furthermore, more abundant wealth enables the development of technological innovations. Nonetheless, it is highly debated whether the environmental Kuznets curve really comes into effect, particularly with regards to ecological damage such as species extinction and land use (e.g. increase of impervious surfaces due to roads and extensions of human settlements).

Right: CO2 emissions (solid line) and GDP (dots) per capita in three selected countries. In all three countries, GDP increased significantly in the past three decades. While in the US and Germany, emissions per capita decreased (absolute decoupling), emissions surged in China (albeit at much lower levels than in the US and Germany).

Still, the goal of the political mainstream in the West, including Germany, Europa, and the US, is green growth. This is reflected in policies of most political parties as well as e.g. the European Green New Deal 5. There is a controversial debate among sustainability researchers and environmental economists whether green growth with absolute decoupling of greenhouse gas emissions (and other environmental factors) and GDP growth is possible. A detailed discussion is beyond the scope of this text, but see e.g. 6. In short, there has been a relative and sometimes absolute decoupling in some western industrialized countries in the past three decades. The speed of the development, however, is by no means sufficient to reach a climate neural, or even eco-neutral, economy in sufficient time (see Figure 2). Moreover, such a development could not be observed in emerging and developing countries.

In conclusion, the ideology of this approach is “Keep at it, but do things differently!”. Humans and their economy are separated from nature. Nature is a service provider for human beings, which we should treat better, but not take into consideration with equal rights. This approach thus follows the conventional framework of our economy and prefers market-based tools (internalisation of externalities e.g. via CO2 emissions trading). We should keep consuming to the same degree and increase our wealth, while technological progress and increase of efficiency in all sectors leads to a more sustainable economy.

Climate researcher Hans Joachim Schellnhuber sees this approach critical and calls our current state the “Omega phase” 7. This is a business term that denotes the ruinous stage of a business trying to solve its problems by intensifying its business model. But what would be an alternative paradigm?

What to do? The revolutionary approach

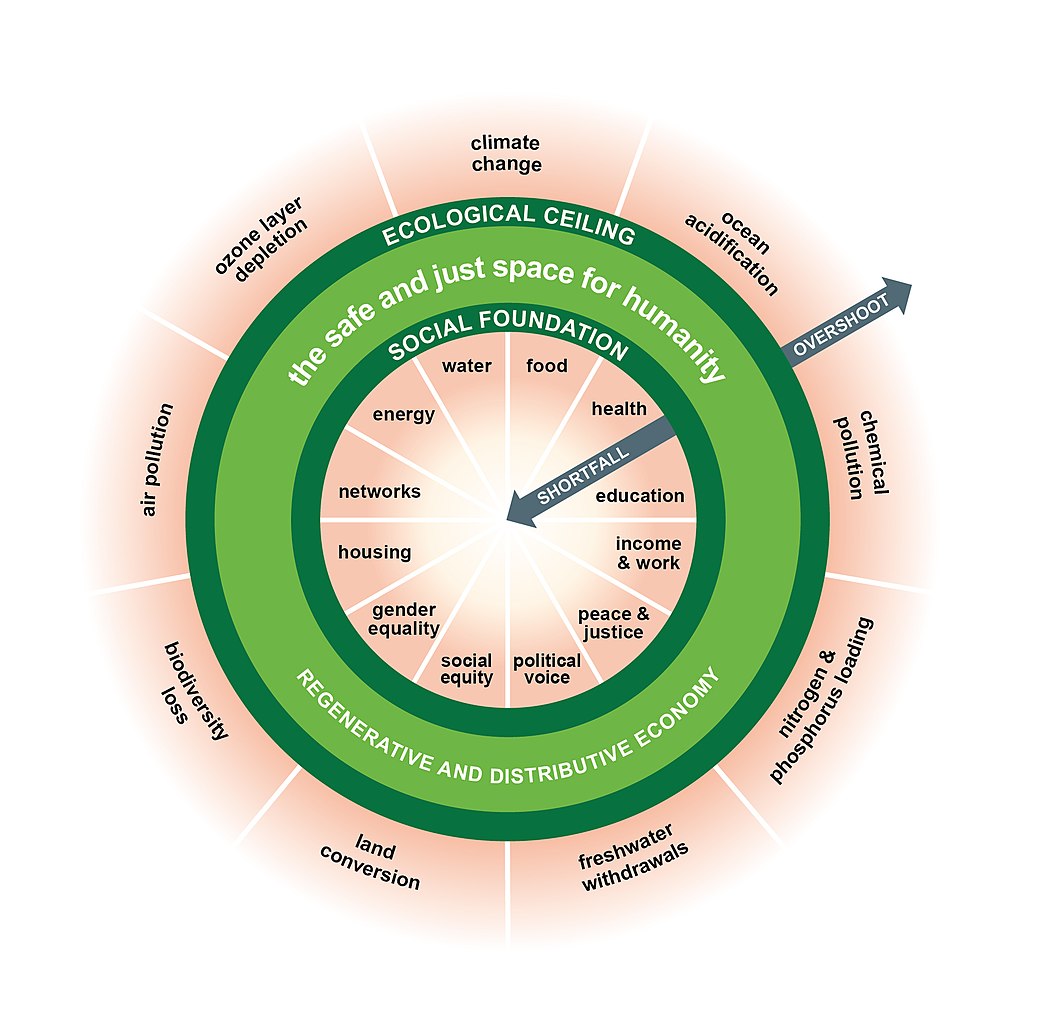

A completely new approach would be to view humanity as an integrated part of the Earth’s ecosystem, rather than being separate from it. Instead of treating the economy and society as superior systems to Nature, they are part of the ecosphere (“embedded economy”, see Figure 3). Human beings are an important factor in the Earth’s ecosystem and their actions have immense consequences on nature on a local and global scale.

At the same time, earth is no longer a passive stage for the civilization of humans, but rather an active agent. In some sense, we return to non-abrahamitic concepts of the world. We can interpret this a logical consequence of the many role changes of humans in the past centuries: from the heliocentric system to the theory of evolution to the non-existence of the free will - humanity has had to accept quite some degradation, why do we still see ourselves as the rulers of nature?

Recently, the concept of “Earth Stewardship” has become popular: humans as manager of the earth with forces so powerful that they, akin to a child that is learning to control its forces over the years, need to limit their applications and control them better. A steward bears responsibility, we as human beings finally need to accept this responsibility and the first step would be to perceive us as integral parts of nature.

This might sound trivial at first sight, but it can have radical consequences:

- An economy that is part of the ecosphere cannot consume unlimited resources and grow infinitely. This view is represented by many growth-critical schools of thought such as the degrowth movement that demands an active shrinkage of the economies in the global North. The Doughnut economy movement 8 takes a more agnostic stance towards growth (“agrowth”): instead of focusing on GDP, it combines the concept of the planetary boundaries with 12 social minimum standards (e.g. supply with education, energy, food etc.). The economy needs to find a middle ground between both (see Figure 3).

- If nature gets a an active role in our economy, it should also have legal rights. Entire ecosystems could be protected with a legal right for intactness. Moreover, “ecocide” could become a criminal offense 9, 10. This would provide the ecological movement a powerful tool for the protection of nature.

- The Circular Economy is another concept embedded in this paradigm. It proposes a transition from our current linear economy (“produce - consume - dispose”) to a circular economy. In the scope of this text, the important point is the analogy to natural cyclic processes: akin to a plant that provides valuable resources to its environment after its death (instead of being disposed), products should be designed such that they don’t lead to any waste. This requires a radical rethinking of product design and business models. For instance, houses would be ideally constructed such that they produce more energy than consumed, similar to a tree producing an added value for its environment (see Cradle-to-Cradle movement 11).

These are only three examples of a bigger upheaval that could result from such a change of paradigm. The most important, however, is: If you perceive yourself as part of nature instead of its ruler or the customer of ecosystem services, you will change your attitude towards nature in a fundamental way. A forest then is no longer a reservoir of timber, valuated in dollars. It is an animate being with a right to live. In Charles Eisenstein’s words:

“That is not to say we should never cut down trees. It is to say that such an act should not be facilitated by an ideology that holds trees—and all life—as anything other than sacred. When we see the forests in terms of board feet or timber value, when we see the oceans in terms of tons of protein or dollars’ worth of fish catch, when we speak of nations as “economies” and people as “consumers”; when we see a place as a source of iron ore or bauxite or gold, when we see these minerals as nothing but minerals, randomly deposited and unrelated to the processes of life around them, when we see a forest or peat bog in terms of its carbon sequestration potential, then we are seeing Earth as a machine, not an organism, dead and not alive. The reason our current system of material production kills the world is that it starts by seeing the world as dead. What then is there to love?” (excerpt from 12).

Conclusion

Obviously it is possible to do environmental and climate protection in our current paradigm and the conservative approach to some degree. However, the problem is that any protection of nature is necessarily perceived as a concession to the external entity of nature and thus needs to be justified every time. In an alternative paradigm that views human beings as a member of nature, this need for justification would be flipped. Instead of fighting with nature, humanity would strive for a positive vision to live in harmony with nature, without giving up the virtues of modern life.

We cannot foresee which narrative will ultimately win. At the moment, the conservative approach and its concept of green growth is likely to have the upper hand because it is political mainstream in Europa, the US and all international institutions. However, it is possible that we will see a true change of paradigm similar to the Age of Enlightenment 300 years ago.

References

1 Rockström, J., Steffen, W., Noone, K., Persson, Å., Chapin III, F. S., Lambin, E., … & Foley, J. (2009). Planetary boundaries: exploring the safe operating space for humanity. Ecology and society, 14(2).

2 Steffen, W., Richardson, K., Rockström, J., Cornell, S. E., Fetzer, I., Bennett, E. M., … & Sörlin, S. (2015). Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science, 347(6223).

3 Yuval Noah Harari, “Eine kurze Geschichte der Menschheit”

4 Yuval Noah Harari, “Homo Deus - eine Geschichte von Morgen”

5 The European Green New Deal: https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en

6 Jackson, T., & Victor, P. A. (2019). Unraveling the claims for (and against) green growth. Science, 366(6468), 950-951.

7 Philipp Blom, “Das große Welttheater” (only available in German)

8 K. Raworth, Raworth, K. (2017). Doughnut economics: seven ways to think like a 21st-century economist. Chelsea Green Publishing.

9 “End Ecocide on Earth - International justice for the environment”, https://www.endecocide.org/en/

10 “Rights of Nature”-Bewegung, https://www.therightsofnature.org/

11 William McDonough, Michael Braungart: Cradle to cradle : remaking the way we make things. Vintage, 2009, ISBN 978-0-09-953547-8.

12 Charles Eisenstein, “Climate - a new story”