Table of Contents

Why are we so passive about the ecocrisis?

When I talk to my friends about the eco and climate crisis, I often come across an attitude that, it seems to me, many share. Yes, we are generally concerned about the climate and the environment. We would also like to live more consciously and do something good. So we try to eat less meat, consume organic products more often and perhaps even consciously save electricity. All in all, however, the climate crisis, or rather the overriding ecocrisis, does not seem too threatening. We will solve it sooner or later, with the help of technical innovations and the right course, all in good time. Haven’t we already survived other crises? The hole in the ozone layer? The forest dieback in the 80s? Sure, I hardly know any real climate change deniers personally. And yet - only a few of us can get up the nerve for real activism.

Why is that? What are the reasons for this relaxed, or perhaps fatalistic, attitude? I believe there are three reasons, all rooted in public discourse. In this text, I would like to explain these reasons in some detail. This text is based in large part, but not exclusively, on discussions with Germans and experiences in the debates in Germany. Nevertheless, I believe that it can be applied to a large extent to other industrialized countries of the global North.

The ecocrisis is not explained well enough.

In order to explain the effects of the climate crisis, a part of the ecocrisis, two variables are essentially used, the rise in the global average temperature and the average rise in sea level. Thus, the general goal of the environmental movement is repeatedly formulated, including in the Paris Agreement, that the increase in the global average temperature should be kept below 1.5 degrees, if possible, and in any case below 2 degrees. Furthermore, it is generally warned that sea levels could rise by up to 1 meter, probably even more, by 2100.

These figures by no means capture the full complexity of the impacts of climate change. Those who do not study the issue in depth and instead hear only these two figures over and over again may think to themselves: what’s all the fuss about? 2 degrees more may mean a little more sweating in summer and less snow in winter, but don’t people in southern Italy live a good life with higher temperatures than in Germany, for instance? A slightly higher sea level, then let’s just raise the levees at the sea and the problem is solved.

Of course, when we look a little closer, the effects of climate change are much more dramatic: first of all, we are only talking about the increase in the average global temperature. It is important to know:

- temperature increases more over land than over water (as of 2019, almost 1.8 degrees compared to pre-industrial times over land and 0.8 degrees over oceans 1).

- in Central Europe for instance, the average temperature will increase much more (at the moment, about 1.6 degrees warming in Germany 2 compared to global 1.2 degrees)

- these numbers describe the annual average temperatures. But more crucial for personal health or e.g. agriculture are the fluctuations in the course of a year. 2 degrees of average warming can mean many more degrees of warming in summer, so that hot spells with temperatures beyond 40 degrees are likely to become the norm 3. In general, extreme weather events such as heat spells, droughts, forest fires, heavy rains with floods, snowstorms, etc. will become much more frequent. For example, Germany has been experiencing droughts for years, which is already causing major problems in agriculture and in German forests.

There is, of course, a good reason for focusing on two numbers: it is easier to communicate them than to present the full extent of the consequences. However, I believe that this kind of communication has taken on a life of its own in recent years, leading many people to dramatically underestimate the consequences of climate change. Instead, we should realize that the 1.5 or 2 degrees represent a future in which the state of the Earth and its climate will become far more unstable than it has been in the past.

One can think of the Earth’s climate as a ball located in a mountainous landscape. This ball is constantly nudged by random fluctuations, causing it to bounce back and forth. After each fluctuation the ball remains in a valley of the mountain landscape. If the ball lies in a deep valley, it will not be pushed out of the valley even by moderate fluctuations. However, if the valley is shallow, even small fluctuations are enough to nudge the ball into another valley and significantly change the Earth’s climate.

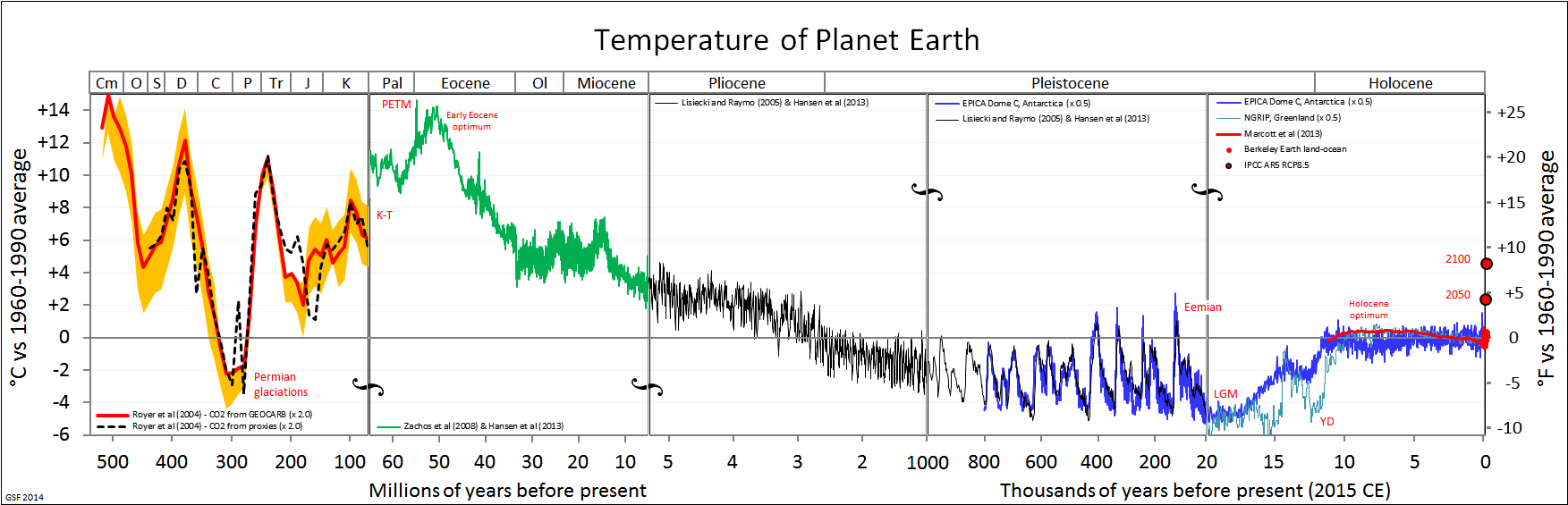

In the history of Earth’s climate, the ball was located in an area of shallow valleys for millions of years and consequently the climate was very unstable with large temperature fluctuations. Only since about 11,700 years ago we are in the Holocene, with a deep valley where the ball is stable, so that humanity could enjoy a stable, very beneficial climate. For example, the development of agriculture, and thus the evolution of humans from wandering hunter-gatherers to sedentary farmers, coincides with the beginning of this era. With the enormous greenhouse gas emissions, we are pounding the landscape with a big sledgehammer, making the valleys flatter and flatter. The climate will therefore become more unstable and dangerous in the future.

Another field is the even more threatening ecocrisis, i.e., the systematic destruction of the environment, which takes place in addition to climate change and interacts with it. Species extinction is part of this ecocrisis and has now assumed such dramatic proportions that scientists are talking about the sixth mass extinction in the history of the Earth (the fifth mass extinction was, for example, the extinction of the dinosaurs). The public likes to illustrate this biodiversity crisis using large mammals such as polar bears or orangutans. So we might think: What do I care about the polar bears at the North Pole or the orangutans on Borneo? And what impact will it have if a few polar bears become extinct?

There are two misunderstandings here. First, animals at the top of food chains, such as polar bears, are essential to ecosystems. They control the population of their prey, whose abundance in turn has massive effects on the rest of the plant and animal world 4. For example, wild animals in Germany’s forests were able to reproduce unrestrained because their natural enemy, the wolf, had long disappeared from Germany’s forests. This leads to deer eating buds and shoots from trees, reducing forests to monocultures 5. The reintroduction of predators can therefore lead to more species-rich and thus more resilient ecosystems. A famous example is the introduction of the wolf into Yellowstone National Park in the United States 6.

Second, it is not only the large predators that are disappearing, but animals at all stages of the food chains that are often even more important to our ecosystems and thus to human survival. For example, a study by the Entymological Association of Krefeld in Germany found that more than 75 percent of the total mass of flying insects has disappeared in the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia over nearly three decades 7. These animals are of fundamental importance for our ecosystems, among other things as pollinators of plants, which enable the growth of fruits on many plants, and thereby production of food, in the first place.

But the response to these shocking news also often shows a lack of understanding of ecosystems: it is not enough to simply put bee boxes everywhere and try your hand at being an amateur beekeeper. The animals also need food, and that means plants. The general trend toward rock gardens (perhaps a German oddity), but especially the barrenness of agricultural land, prevents this.

To summarize these two points, we need to better understand how ecosystems work. Nature is a complex system, but it is too often understood as a kind of machine whose individual components need to be repaired from time to time. In reality, however, things are much more complex and everything is connected to everything else. It will not be enough to simply reduce CO2 emissions or put up more bee boxes.

The polemical discourse (at least in Germany).

If you follow the discourse in Germany on the environment and climate, it is striking that there are really only two gears: Either there is a polemical discussion exclusively about the possible negative effects of environmental policy measures, or there are very small-scale discussions about the details of individual steps. There seems to be no middle ground although that’s exactly what we need: an honest debate about the effects of the climate crisis and the risks we are taking with our current way of living and doing business.

There is no point in oversimplifying this discussion (see above) or skipping it and instead arguing about whether the CO2 price should be 65 euros from 2023 or 66 euros from 2024. Such discussions must be held, of course. But they are unsuitable for convincing voters or highlighting the differences between political parties and only lead to confusion.

On the other hand, the ongoing discussion about meat prices or vacation flights is also unfair framing that turns off many. It is a popular game to overemphasize the unpleasant consequences of environmental policies and put the positive consequences in the back. An example: organic framing, which better integrates nature, uses less pesticides and creates habitat for insects, and thus makes the continuation of food production possible at all? To this, the German news magazine SPIEGEL can only think of the question: “Will a kilogram of beef soon cost 80 euros?” 8.

Instead, we need a debate about what life in our countries should look like in 10, 20 or 50 years. Do we still want to preserve what little nature there is? Or do we want to continue to occupy more and more space with settlements, highways and parking lots? Do we want to stick with the current way of doing things for as long as possible until it is no longer possible, or do we want to actively shape change?

Based on this, we need to discuss how these goals are to be achieved. With purely market-based instruments such as emissions trading? Or supported by regulatory measures such as a ban on internal combustion vehicles or short-haul flights? How can we combine environmental protection and social policy? Clarifying these questions without getting bogged down in tedious details or the usual platitudes of conservatives and the right would be extremely important.

These are the important discussions that we need to have, and these are also the differences along party lines in politics (at least in Germany). At the same time, this is a level where people can participate in discussions without detailed expertise. In this way, more people would certainly feel more involved and addressed.

The global scale is paralyzing us.

The ecocrisis is a scary topic to deal with. The scale of environmental degradation is shocking and the effects of the climate crisis visible around the world. The challenges of the climate crisis are global; we need to reduce emissions around the world to zero (or even negative) to stop the earth from heating up. This global scale can be intimidating and paralyzing: What difference can I make as an individual? What impact can a policy change in Germany, which is “only” responsible for just under 2 percent of global emissions (insert your country and its numbers here at will), have?

Opponents of environmental protection like to exploit this paralysis to justify political stalemate. Their strategy is clever: in order to divert attention from their own failures, they try to pass on the pressure in two directions at once. On the one hand, they stress that climate change can only be averted at the global level. On the other hand, they emphasize the responsibility of the individual consumer. If only everyone would finally eat organic meat, buy electric cars and separate their waste, the problem would be solved. The concept of the individual carbon footprint which was invented by the oil industry to divert attention from its own systemic responsibility 9 is a good example of this strategy.

As a result, the crisis is, paradoxically, being globalized and individualized at the same time. The recipient is left with the impression that political activism is not worthwhile, since the problem can only be addressed on a global political level. At the same time, they are given the personal responsibility to point the finger at themselves. I don’t want to say that individuals should not change their behavior, because every step is useful. But the crisis will not be solved by changing patterns of consumption.

Shifting the responsibility to the individual has yet another purpose. It prepares the usual “ad hominem” argument against environmental activists: if an activist is “caught” eating meat or boarding an airplane one day, environmental opponents defame him as bigoted and hypocritical. But it would be the task of politics to make environmentally friendly behavior easier. No one should be forced to become a martyr in order to consume sustainably 10. And one is also allowed to participate in social life as an activist.

But there is a way out of this dilemma, because action against the ecocrisis and for nature can and should take place on many levels. From individual behavior to local initiatives to political engagement in parties to influence state, federal or even European politics, we need to be active on all of these levels. However, in my opinion, the local level offers the best relation between personal influence (and effort) and benefits to environmental protection.

In his book, philosopher Charles Eisenstein describes how local and regional action can bring about effective steps against the climate crisis 11. In doing so, he provides numerous examples of how the restoration of local ecosystems can at least mitigate, and often even reverse, the effects of global warming. Ecosystems such as wetlands (peatlands, mangrove forests, etc.) and forests are the most effective CO2 stores there are. When we talk about negative emissions, we need to bring back these landscapes. Germany in particular is a country that was once rich in peatlands. However, these were systematically drained in order to extract the peat and use the land for agriculture. The good news is that these landscapes can be renaturalized. Sometimes all that is needed is to remove the old drainage pipes.

Such ecosystems are not only good at storing CO2, they also provide us with the most important substance we need to live: Water. Forests store moisture and evaporate it back out, leading to cloud formation and thus precipitation. Forests thus generate regional climate and protect entire landscapes and regions from drought. So we can do something very concrete to combat the increased risk of drought caused by climate change, and we can do it on our own doorstep. Incidentally, this also leads to lower temperatures, which is why tree planting in cities is an important means of preparing our cities for the hot future. Another aspect is the destruction of natural river landscapes. Rivers absorb precipitation and carry water to the sea. River straightening and concrete river beds accelerate this process, destroying local riparian landscapes where water can percolate and ultimately leaving less water on the land, contributing to drought.

In extreme cases, this creates deserts, and indeed humans have contributed significantly to the formation of the Sahara 12 and the arid landscapes in the Middle East 13. The Great Green Wall Initiative 14 builds on this knowledge and has set itself the goal of drawing a green ribbon across Africa, thus greening the desert once again. But we don’t have to look to Africa: in Germany (and most likely in your country), too, ecological devastation with monocultural forest plantations instead of forests, straightened and concreted rivers, and drained bogs has caused drought to become more widespread.

So the answer to the paralysis caused by fixation on the global and individual scales is: local engagement pays off. Local initiatives that demand environmental protection on the ground and care for the preservation and renaturation of landscapes contribute to the fight against global warming and its consequences at least locally, often regionally and even globally through CO2 storage.

Conclusion

In my eyes, we can get many more people into activism against the ecocrisis if we address these three points. The environmental movement needs to better communicate knowledge about the eco- and climate crisis, freeing itself from fixation on average temperature. More knowledge about ecosystem function is fundamental. Furthermore, public and private discourse must choose the right level of description. Instead of chewing over small-scale details over and over again, we should focus on the big questions: how do we want to live in the future, what is important to us, and how do we see our relationship with nature? And what are the appropriate tools to achieve these goals?

And finally, we must free ourselves from the paralysis that the global scale of the crisis has brought us. Instead of pointing at other countries, focus on nature at your own doorstep, protect and help restoring it. For example, one can get involved in local environmental protection projects, get involved in local politics through political parties, or support or initiate a local climate initiative.

In this way, the transition from passive consumer to activist can succeed and we can move from lamenting and passive complaining to doing. And this is what is desperately needed to preserve our future.

References

1 https://www.carbonbrief.org/state-of-the-climate-how-the-world-warmed-in-2019

2 https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/07/01/germany-inaction-heat-plans-threatens-health

3 https://www.c2es.org/content/heat-waves-and-climate-change/

4 This theory is called the “Green World Hypothesis”. It addresses the question: why is our world green, why don’t all plants get eaten by herbivores? To this end, it postulates that the abundance of herbivores is controlled by carnivores at higher levels in the food chain. It has been confirmed in various experiments.

5 https://www.forestresearch.gov.uk/news/understanding-deer-damage-crucial-when-planting-new-forests/

6 https://www.yellowstonepark.com/things-to-do/wildlife/wolf-reintroduction-changes-ecosystem/

7 https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2017/10/germany-s-insects-are-disappearing

8 https://www.spiegel.de/wissenschaft/natur/zukunftskommission-landwirtschaft-kostet-ein-kilo-rindfleisch-bald-80-euro-a-a0634de3-934c-4bce-97b3-581c93362e32

9 https://mashable.com/feature/carbon-footprint-pr-campaign-sham

10 An example from Japan: If one wants to live strictly vegetarian here, it is basically impossible to go to a normal restaurant, because even vegetable dishes are made on the basis of fish broth and pure vegetarian dishes are extremely rare. Since social life here takes place almost exclusively in restaurants, this means social isolation. This may be different in your country, but try to completely avoid unnecessary plastic packaging. Going to the supermarket becomes simply impossible. Or try to get around without a car in the United States.

11 Charles Eisenstein, “Climate - a new story”

12 Weisman, Alan (2008): »Africa after Us: What Effects Have Human Actions Had on the Sahara—The World’s Largest Nonpolar Desert?« in: The Globalist, 26. 01.

13 Hughes, J. Donald (2014): Environmental Problems of the Greeks and Romans: Ecology in the Ancient Mediterranean. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore